Forced Removal and Mass Incarceration

On December 7, 1941 the Empire of Japan attacked the U.S. Navy base at Pearl Harbor, causing the U.S. to enter the Second World War. This sudden commencement of hostilities sparked intense anti-Japanese rhetoric that made no distinction between Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans.

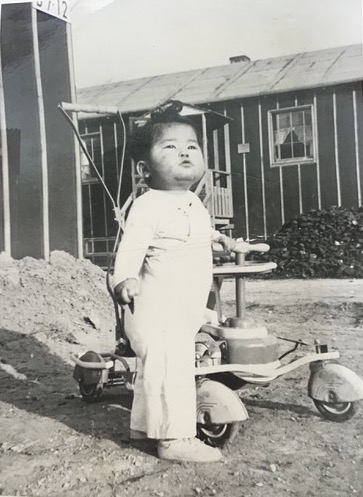

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which gave the military authority to exclude any persons deemed capable of sabotage from designated military zones on the West Coast. EO 9066 would set the legal precedent for 125,284 persons of Japanese ancestry to be forcibly removed from their homes. Anti-Japanese propaganda suggested that the Nisei might have conflicted loyalties solely because of their heritage. They were imprisoned alongside their immigrant parents in incarceration camps, euphemistically called “relocation centers,” located on desolate federal land in arid mountain plains, deserts, and swamps with armed guards, barbed wire fences, and searchlights. 1,862 of those imprisoned died under their inhumane conditions.

Relocation to Philadelphia

In December 1944, the Supreme Court justices released an unanimous ruling Ex Parte Endo that the US government could not continue to detain a citizen who was “concededly loyal” to the United States. This did not free all wrongfully incarcerated Japanese Americans, but it laid the foundation for the camps to be closed. A resettlement program began to find new homes for the Japanese Americans who had nothing to return home to on the West Coast. The Quaker-led American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) supported Japanese American efforts to relocate to Philadelphia, the third largest city in the United States at the time.

In 1942, AFSC and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) created the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council headquartered in Philadelphia. The organization secured college placement for eligible Nisei students to attend local universities. The WRA regional office also helped working adults find employment in Philadelphia, which was a precondition for their release from camp. By 1946, about 7,000 Japanese Americans had chosen Philadelphia as their new home.